Sudan: The Tragedy of the Forgotten Conflict When There Was Once Hope

The forgotten conflict

Africaand the world have seen so many major conflicts in recent years, which have held the attention of the international media. The suffering in Palestine, and the Russia-Ukraine war. In Africa, the insurgency attacks in northern Mozambique and the Sahel. The fighting between armed groups in eastern DR Congo. Ongoing strife in Somalia. Ethiopia’s civil war.

While a few reports still come in on the conflict in Sudan, that tragic event has been largely ‘drowned out’ by the flood of news mainly from the ruins of Palestineand the battlefields of Ukraine.

The current situation in Sudan

The Sudanese Armed Forces(SAF) are led by General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Services (RSF), are led by al-Burhan’s former deputy, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (nicknamed Hemedti). The two groups are locked in a combat stalemate.

The SAF has the advantage of air power and the apparent support of Egypt, while the RSF is limiting SAF air power with effective anti-aircraft artillery. The RSF reportedly has the support of the United Arab Emirates. The civil war (which is playing out mainly in the capital city of Khartoum), began in mid-April 2023. At the time of writing, the SAF holds much of the capital city of Khartoum, while the RSF has captured the presidential palace and the international airport. In a recent development, the SAF has recaptured the radio and television centre.

Perhaps the SAF is gaining some ground in Khartoum, but the war is also largely being conducted in the nearby city of Omdurman and the South Kardofan State as well as the troubled western region of Dafur, where the RSF has control.

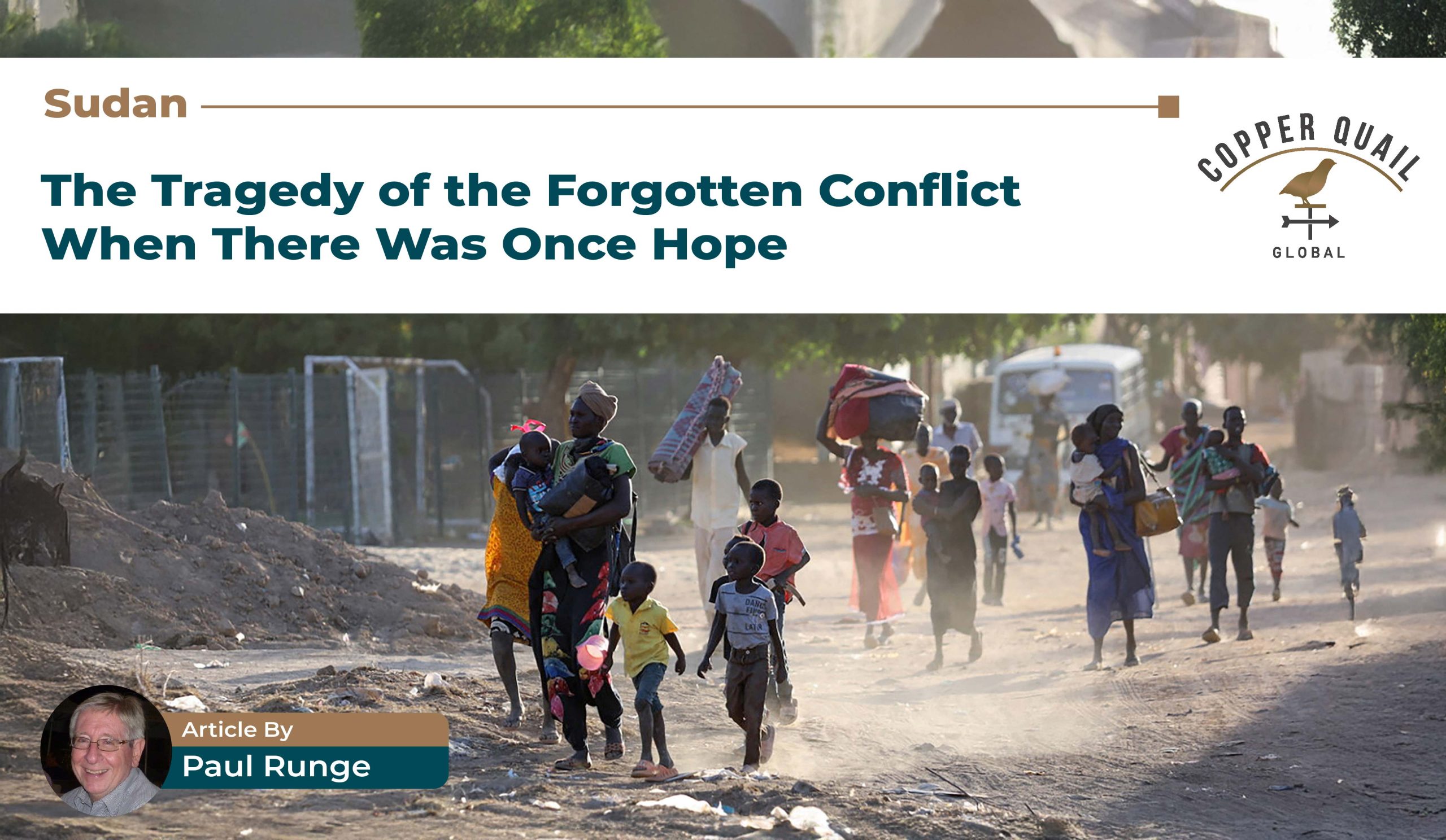

Terrible effects on the population

The war damage statistics are horrific. It is estimated that nearly half of the population (25 million), are now in need of humanitarian assistance; eight million have been displaced; 1,8 million have fled to neighbouring countries (notably Chad, but also South Sudan, Ethiopia, Egypt and Eritrea); and over 14000 have been killed. Various relief aid agencies, such as the World Food Programme, are issuing urgent calls to the international community for funding assistance.

But there was a time of peace and hope

In April 2003, I was a member of a high-level South African business delegation that dropped into Khartoum for a two-day visit. We were given VIP treatment from the moment we touched down in our executive jet. We were ushered into the airport VIP room, and transported to our Hilton Hotel in limousines protected by motorbike outriders. In the evening, we were the guests of honour at a cocktail event held on the banks of the White and Blue Nile rivers’ confluence. Our itinerary included a long meeting with the Sudan minister of finance, as well as a visit to a new oil refinery situated some fifty kilometres outside Khartoum.

It was a time of peace and hope. The economy, under the long-ruling President al-Bashir, was registering a growth rate of over 6%. This growth was bolstered by revenues from new oil developments, and daily production had reached over 250 000 barrels per day. Relations with the donor community were improving, and negotiations with the International Monetary Fund were afoot. On the international level, peace negotiations with the then-Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) that would finally result in independence for South Sudan in 2011, were well underway. The al-Bashir government was under economic sanctions by the USA due to accusations of supporting international terrorism. But now there was even some talk of rapprochement, an end to the sanctions, and acceptance of the regime by the USA.

The minister of finance impressed our delegation. He gave what seemed a realistic view of the country’s future and did not hold back from referring to the possible future pitfalls.

But the war in Dafur began in 2003, leading to the formation of the RSF (formed out of the Sudanese Arab militia group, the Janjaweed), who ruthlessly suppressed the local population in this western region of the country.

The fall of strongman al-Bashir and a second period of hope

On 11 April 2019, al-Bashir was overthrown in a military coup. This event was preceded by a year of mass popular protests sparked by steep rises in the bread price and the ill effects from the devaluation of the Sudanese Pound. These negative developments led to demands for democratic reform.

Negotiations between the Sudanese political parties and the military began in mid-2019. The Transitional Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change agreed to a 39-month process of return to democracy with the establishment of legislative, executive and judicial institutions and frameworks. A civilian prime minister and largely civilian cabinet were subsequently appointed. Agreements were concluded with Sudanese rebel groups, and in February 201, a fragile government under former United Nations official Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok was formed.

Although there was still much unrest and anti-military protests, and a coup attempt reportedly instigated by parties linked to al-Bashir’s overthrown government, there was hope that Sudan was heading towards a tenuous democracy.

But in January 2022, Prime Minister Hamdok resigned when he failed to name a government amid continuing popular and bloody protests over the slow progress to democracy. The ‘revolution’ that had unseated al-Bashir had faltered, and the protestors were calling for ‘another revolution’. There was the contradiction of civilian rulers sharing power with the militia responsible for the human rights violations that led to the initial protests. Popular support for the transition was waning.

Then the steep fall into chaos

On 15 April 2023, fighting broke out in Khartoum between the SAF and the RSF, and all hopes for a democratic solution died. The catastrophe rapidly worsened and the World Food Programme has since warned that ninety percent of Sudan’s population is confronted with emergency levels of hunger. The situation is described as one of the fastest growing crises in the world. Numerous cease-fires between the two warring parties have been declared and then broken.

Media interviews with ordinary citizens left behind in the war zones reveal a fatalistic view: “This is an experience we must go through to have a better future”, and, “We can only place our hopes on higher interventions from God.”