Guinea: Home of the Last–Known Biggest and Richest Unrealised Iron Ore Deposit in the World

An exciting invitation for a mission to a country blessed with resource wealth

It was late 2012 when a long-standing client invited me to assist him with a mission to Guinea investigating a proposed major rail line in that West African country. I gladly accepted, because I had never been to Guinea but had learned that it is particularly rich in mining resources. This is the world’s second–largest bauxite producer – a precious material used inter alia for production of aluminiumand steel. Relatively unexploited iron ore, uranium, gold and diamonddeposits can be added to the more established bauxite production.

But also with a history of political disruptions

Just prior to independence in 1958, Guinea’s first president, Sékou Touré, angered France when his country voted for complete independence as opposed to autonomy within the French Community – a rare move among Africa’s other French colonies. A further manifestation of Guinea’s desire to break completely from the colonial power was its adoption of its own currency, the Guinea Franc. (The French-backed CFA Franc is still utilised today by almost all of France’s former African colonies.)

The years following Touré’s death in 1984 saw considerable political turmoil. At the time of our mission, the former opposition leader, Alpha Condé, had recently been elected as Guinea’s fourth president. There was considerable optimism at that time that the country had stabilised and that economic progress would result. (However, political disturbances continued and in September 2021, an army lieutenant-colonel took power and dissolved the Condé government.)

Discovery of a huge but ‘stranded’ iron ore deposit peaks the interest of big miners

The Simandou iron ore deposit was discovered relatively recently, in 1997. It lies inconveniently in a far mountain range in the south-east of the country. Estimates of the recoverable iron ore reserve vary between 2,4 billion and 4 billion tons. The quality of the ore is high, with gradings estimated at above 67%.

The discovery brought much excitement from the Guinean authorities and strong interest by some of the major mining houses. The four designated blocks are held by a melange of interests including Chinese and Singapore groups, and several multinational joint ventures.

Rio Tintoof Australia has been a strong participant throughout the years since the Simandou discovery. Changes of government, disputes and contestations over mining rights have until recently, effectively blocked the development of Simandou. Vale of Brazil has resorted to international arbitration over its concession rights.

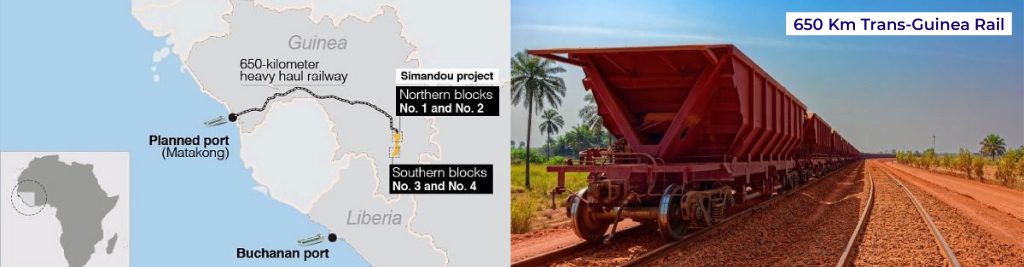

A major reason for the delay in realising the Simandou project has been its difficult geographic location. Guinea’s sovereign territory is shaped like a boomerang, with the Simandou deposits located in the far south-east corner – effectively land-locked and ‘stranded’ some 350 kilometres from the Liberian coast. The Guinean governments have long insisted on the evacuation of the Simandou iron ore via a lengthy rail line that traverses Guinean territory only.

The option of using the shorter routes to the ports of Liberia in the south has been refused. Accepted plans include the construction of a new deepwater port situated south of Conakry, which will be linked to the rail and designated to handle the shipping of iron ore from Simandou. The cost of the two projects comes to a whopping projected total of up to US$ 20 billion.

Our mission discusses the Simandou challenges with the Guinean authorities

Our mission delegation comprised four experienced South African rail experts and myself. It was an intense visit involving meetings with the ministries of mines and transport, the national mining and railway companies, and the mining houses. Included was a visit to the railway workshop. We soon acquired useful insights into the country’s rail sector.

The main question we posed to the officials was why they did not wish to establish an operational rail link between the Simandou mines and the port of Buchanan in Liberia?. At about 400 kilometres, the Liberian route would be far less costly than the 650 kilometre Trans-Guinea railto which they were so committed. The routing of the new railway was another complication.

It would run close to the borders with Liberiaand Sierra Leone, and (to the best of our knowledge,) Guinea’s borders with it southern neighbours were not clearly defined. It was obvious that construction of a new port instead of the expansion of an existing port was also an expensive initiative. Our more technical questions related to their insistence on a standard gauge rail line when a narrower gauge would suffice.

However, it soon became apparent to us that the plan for a standard gauge line traversing Guinean territory to a new port was not to be questioned. The government wanted to ensure complete ownership of the mining production and the support infrastructure. The African regional organisations were also all insisting on standard gauge for all new railways, albeit that metric gauge could sometimes suffice.

Yet, despite all the challenges, recent developments indicate that Simandou could eventually happen…

There has been a flurry of recent activity that indicates new impetus for the realisation of this major project.

In early 2021, early works began on the rail line. In July 2023, Rio Tinto signed a US$ 300 million agreement with the Portuguese contractor, Mota Engil, for the acceleration of mine construction in their blocks. In August 2023, Rio Tinto concluded a US$ 224 million earthworks contract with the Chinese Overseas Engineering Corporation. Latest announcements have been made by the SMB-Winning Consortium and Rio Tinto, indicating agreement on their collaboration on the construction of the rail and port.

Simandou may well be regarded as a ‘ring-fenced’ project. This is to say that despite political uncertainties, logistics challenges and high costs, the sheer economic scale and consequent financial viability of the venture could propel it to realisation. It is a project of unprecedented size for Guineaand the region. The developers will have to ensure on a continuous basis, that they meet the numerous environmental requirements relating inter alia to population displacement, deforestation, food security threats and water source contamination.