Nairobi: A Major Centre for Regional Relief Aid

Sound advice from an experienced ‘old hand’ in United Nations relief aid

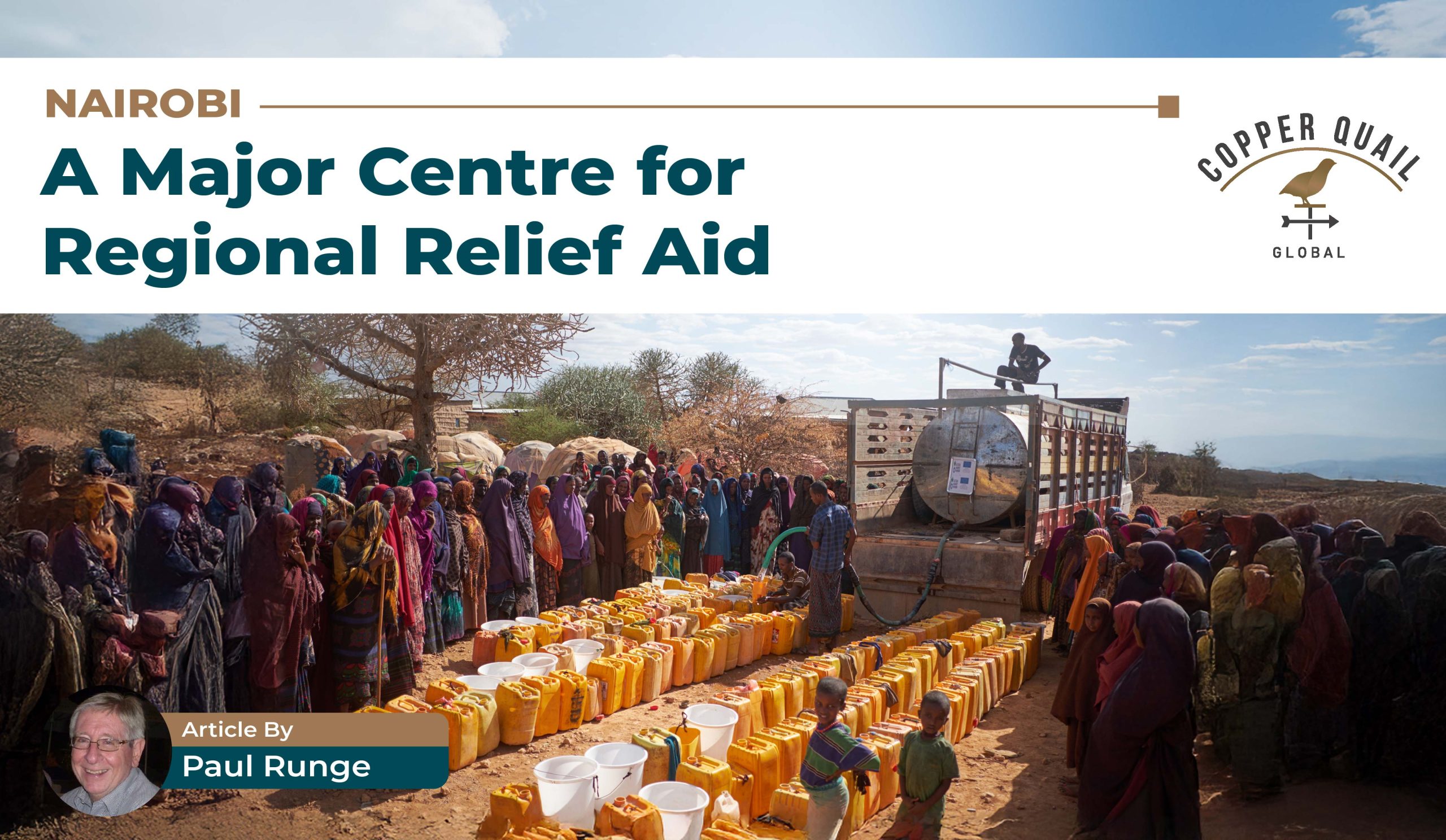

“Paul, you must tell your clients loud and clear that if we don’t get the right stuff to the right place in the right time, people die! In this business, we can’t play games.”These were the words of a good friend who has spent many years as a procurement officer for a major United Nations agencyresponsible for relief aidoperations in Africa.

What is ‘relief aid’?

What is ‘relief aid’ compared with other forms of aid? It is basically urgent assistance in the form of funding, goods and services provided to people affected by naturaland man-made disasters, and other negative developments such as floods, drought, war and economic and social turmoil resulting from conflict. The aid required is urgent, and follows a relatively sudden calamitous event or a situation of particularly dire and life-threatening nature.

Relief aid differs from other forms of aid which entail programmes and projects that are planned and implemented over pre-determined time periods for a longer-term benefit to the targeted communities, countries and regions.

The special role of Nairobi in the African ‘relief aid’ scenario

Africa as a continent is unfortunately continually plagued by climatic calamities as well as conflict. The African Union estimates 115 million Africans are in need of humanitarian assistance. These events may occur relatively suddenly, such as the civil war in one of Africa’s richest countries (Libya), genocides (Rwanda), or insurgencies (Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado Province). However, there are certain countries and regions where turmoil and suffering have been long-lasting and almost constant: the Eastern DR Congo, Somalia, the Sahel region.

Kenya’s location in the centre of the East African region places it in proximity to conflicts that have been both relatively recent as well as long-standing. In the past months, Ethiopia and Sudan have experienced major turmoil. The situation in South Sudan has recently improved, but the population remains in need of urgent assistance, especially food aid. Reports of conflict in the Eastern DR Congo have for a long time been almost continuous.

Nairobi is generally acknowledged by many aid organisations and regional non-governmental organisations as a logistical hub for the region. The city abounds with the local and regional offices of United Nations agencies and a myriad of civil society organisations. Most international companies choose the Kenyan capital as their headquarters for their East African operations.

My mission

My mission was to canvass Nairobi-based UN agencies and NGOs and persuade them to participate in a buyers-sellers forum and networking lunch at a Pan-African Health Congress to be held in Johannesburg. The event included an exhibition of goods and services required for relief aid operations.

The goods would include items such as mosquito nets, brick-making machines and agricultural tools while the services revolved around supply logistics with specialised information technology programmes. This would be an opportunity for the appropriate manufacturers, traders and service providers to meet with key UN and NGO staff members such as the procurement and logistics officers.

Harassing the UN agencies

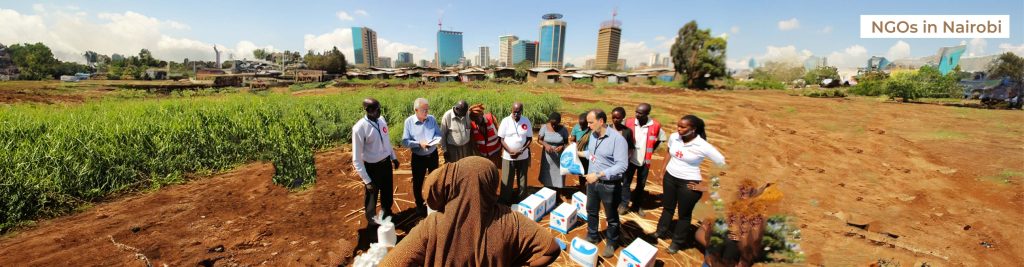

Many of the UN agencies are found in the UN headquarters in Africa, which they call the ‘UNON (United Nations Office at Nairobi) compound’. These include those providing relief aid such as the United Nations Childrens Fund (UNICEF) and the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN (FAO). It is situated in the Gigiri suburbon the outskirts of Nairobi. At the entrance to the complex is a large sign which reads KaribUN(Karibumeaning ‘welcome’ in Swahili.)

I am told that there are over 4 000 UN staff members operating in the many multi-storey buildings in the compound, representing the many UN agencies, funds, programmes and secretariat. They’ve certainly established a comfortable working environment for themselves. There is a gym, banks with ATMs, a clinic, post office and courier service centre, a travel office, a fuel station with a convenience shop, and even a conservation area on the border with wildlife and indigenous vegetation where the staff and their guests can walk.

The UN is a highly regulated and structured organisation. The reply I received from some of the agencies was, “Sorry, but most of our big orders are made from our global headquarters.” Others indicated that there was an opportunity for my clients, but they all strongly emphasised that prospective suppliers had to register with each agency, and that suppliers must meet the specific requirements and standards prescribed by the various agencies. It was important for applicants to familiarise themselves with the UN procurement modus operandi. The introduction of new products and services would require considerable examination and formalities before these could be approved.

The impression I gained from my UN meetings was of (understandably), considerable reliance on long-standing suppliers who had proved their credentials. It would sometimes be difficult for a newcomer to supplant established suppliers.

And now for the NGOs

There are very many NGOs in Nairobi, and I had to sift through the long list to identify those substantially involved in relief aid who would thus be more suitable for the events I was promoting. I undertook a three-day whirlwind visit programme that included major NGOs such as World Vision, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and Oxfam. The programme included smaller, specialised organisations such as AMREF (which concentrates on the medical sector) and KickStart (with the motto, “Tools to end Poverty”), which researches and designs irrigation implements for distribution in poor, rural areas.

These non-governmental aid organisations were generally less formal than their UN counterparts (with whom many work closely), and are more open to accepting proposals for new innovative product and services. But they, too, stressed the need for supplier conformity to their specifications and standards.

In the end, it’s still people who count

I met many procurement officers, logistics specialists and agency representatives during my Nairobi visit. Some were stiff, formal and difficult to convince, while others were open, friendly and apparently interested in my proposals.

No matter how much formality and rigidity these agencies practise, I knew that the individual contact and rapport I achieved with some of their representatives would stand me in good stead – not only for acceptance of participation in the events, but also for future business collaboration and possible supply by my clients.

Not easy, but the longer-term benefit is great

I had a client who manufactured hand-operated water pumps. I introduced the client to one of the relief aid NGOs which expressed the need for this product. The small company spent months and incurred considerable expense in first registering and then adapting its water pumps to the design demanded by the NGO. However, the resultwas a major, ongoing supply contract that has led to the doubling of the size of the water pump manufacturing plant. Today, the company is better defined as a medium-sized enterprise.