SENEGAL SETS THE EXAMPLE FOR AFRICA WITH EFFICIENT WATER SUPPLY DELIVERY IN A SEMI-ARID AREA OF THE CONTINENT

A WATER-STRESSED REGION…

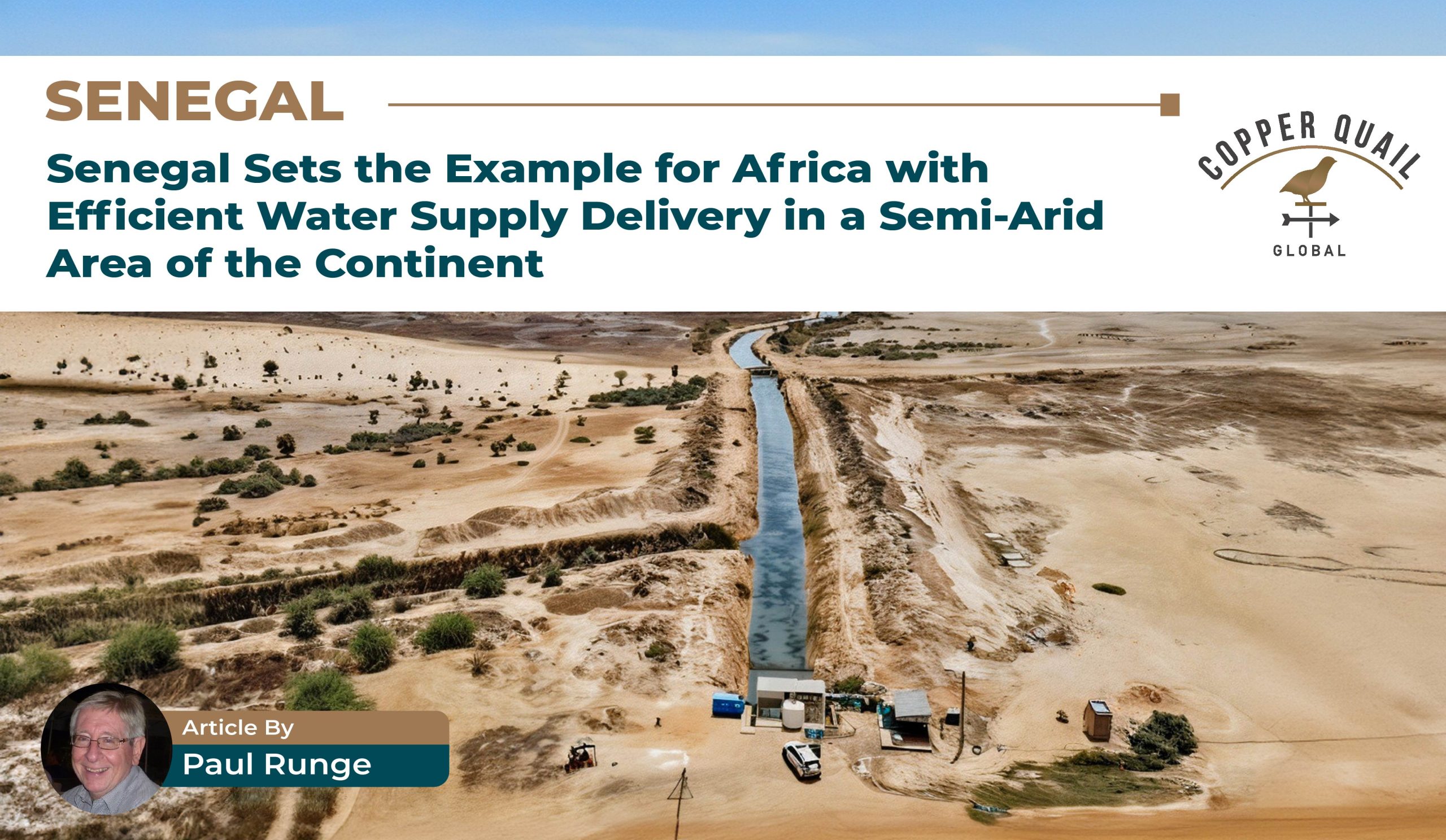

At over three million square kilometres, the Sahel region stretches from Senegalto Sudan, and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, traversing the countries that lie south of the Sahara Desert. It is a hot and arid area, long-plagued by drought and desertification. Water supply is a major ongoing challenge for its fast-growing population of around 170 million (a figure which depends upon the definition of Sahel countries and areas.) It is predicted that this population could double within the next 22 years.

A SPECIAL ASSIGNMENT…

A prominent global non-governmental organisation has approached my company and our research partners to undertake a study of the water sector in Senegal. I am to travel to Senegal to investigate potable water supply in the capital of Dakar, and to obtain information on donor-funded programmes dealing with drinking water supply to the rural areas. The assignment includes interviews with Dakar residents on their day-to-day experiences in meeting their potable water needs.

Our initial pre-visit desk research soon reveals that within the context of water supply, Senegal is a particularly interesting and unique Sahel country.

Senegal has a high level of access to water services compared with other sub-Saharan African countries. It is estimated that 81% of its population have at least basic access to water, that efforts at privatisation of water and sanitation services have met with some success and that there is considerable support from the donor community. But there are problems too. There is a concerning gap between urban and rural supply. The rural areas and the south in particular, are under-supplied. Only a small percentage of urban dwellers receive satisfactory sanitation services. The population growth and increase in economic activity indicate that water supply will become a major future challenge.

Dakar is supplied by groundwater aquifers, and by plants that pump water from Lake Guiers, some 250 kilometres to the north. These aquifers are reportedly overused and being depleted.

HITTING THE STREETS OF DAKAR AND BUMPING INTO REALITY…

There are vendors selling sachet water everywhere—men and women with plastic buckets balanced on their heads, moving between the traffic. Drivers and passengers stretch out their hands to receive and pay. Business is brisk and there are many discarded plastic sachets lying on the street. I pick up one. The brand has the fancy name of ‘Si Belle’ (so beautiful), with a picture of a snowy mountain in the background. I ask the buyers why they are purchasing ‘plastic water’.

Most answer that they do not trust the tap water supplied by the city utility, and bottled water is too expensive. I am directed to the mini-plants located in the streets that supply the product. I see machinery operating in the interior behind them but the suppliers will not let me past the front office to see their equipment. Their answers to my questions are guarded, and I have the idea that they think I am spying on behalf of their competitors. I am told by officials that many of these small manufacturers are unregistered and uncontrolled, and that their water often does not meet sanitary requirements.

The used sachets lie everywhere and are clearly a pollution problem. I am therefore gratified to hear that following my visit, the government has banned production of single-use plastic sachets.

I interview many people. The pharmacists tell me that they stock water purification tablets, but that demand is not very high and it’s mainly the expats who buy them. The equipment stores tell me that the wealthier Dakarois buy filters and pumps for their home systems. A young entrepreneur tells me that he’s doing well by selling recyclable water containers. An old man is selling buckets filled from his borehole.

A group of young Senegalese interviewees have been arranged by an agent of my NGO client. “We sieve the tap water through cloth. We leave water to stand in buckets, let the sediments sink to the bottom and use the water at the top. We boil water for old people and babies. I use Jik Javel to clean my water. If we don’t catch our rain water, it disappears very quickly into the ground. ”

I visit some suburban homes. They show me their rooftop tanks that feed water through pump and filter systems into the houses. They complain about levies imposed by the private company which has been appointed by the government to distribute water to them.

A representative of a bottled water company remarks that, “The water in Dakar is perfectly drinkable, but there will always be the perception of a need for safe drinking water.”

A RARE WATER SECTOR PRIVATISATION SUCCESS…

So many attempts at water sector privatisation initiatives by governments have failed. As a basic human right, water supply will always be complex. However, Senegal seems to have achieved some degree of success.

At the time of my assignment, there were three main utilities falling under the Ministry of Water and Sanitation: the Société Nationale des Eaux du Sénégal (SONES – the national company); Sénégalaise des Eaux (SDE – the private partner in a Public Private Partnership); and the Office National de l’Assainissement (ONAS – the state sanitation company).

Water sector administration in Senegal is unique, and is regarded by many as a model to be copied by the rest of the sub-continent. Senegalese government officials have claimed that SDE is the first example of water privatisation in the world. Despite complaints from the population that SDE water rates are too high, the state-appointed private operator (operating on a Pubic Private Partnership basis), has done well. From 1996 to 2014, water sales increased substantially to over 130 million cubic metres per annum, and by 2010, about five million customers were reached.

Surveys showed that customer satisfaction was relatively high, and there was appreciation for the introduction of new technologies that improved client services. In 2002, SDE was the first African water utility to receive ISO 9001-2008 certification.

Another unique feature is the creation of a national sanitation company which collaborates closely with the private sector and is generally well-regarded by the business community.

In 2020, the Suez Group of France took over from SDE and jointly manages potable water operations and distribution in urban and peri-urban areas. Sen’Eauis a company that is majority-managed by Senegalese in partnership with Suez and now acts as technical partner and distributor.

NO SHORTAGE OF DONOR AND NGO AID AND ASSISTANCE…

Senegal’s relative success in its water sector was partly due to strong donor and NGO support, and has attracted further favourable attention from these agencies. They have and are implementing numerous programmes, projects and initiatives.

The Potable Water and Sanitation Programme (French acronym: PEPAM), is particularly noteworthy in that covers the extensive rural areas of the country and depends on community and private sector involvement. It is strongly supported by numerous donors including the African Development Bank, the World Bankand the European Investment Bank. The Africa Development Bank is responsible for programme implementation in the least developed southern areas of the country.

Under PEPAM, hundreds of user associations or ASSUFOR’s were established in rural communities. These associations were trained in hygienic practices and given responsibility for maintenance of wells and water sources, distribution and liaison with suppliers of equipment and technical assistance. The programme has achieved success in improving water supply as well as general health among Senegal’s rural population.

SUCCESS BUT FUTURE CHALLENGES…

Senegal’s population is increasing at just under 2,6% per annum and Dakar’s growth is higher at 3,1%. There are obvious additional strains on water supply. A World Bank report states that water usage could increase by up to 60% by 2035. The strong dependence upon groundwater exposes the population to the limitations of overuse and pollution. Dakar city requires more sanitation services. The southern areas continue to be particularly water-stressed. Lake Guiers is also supplying irrigation water and may limit its potable water supply.

However, at least Senegal has established the enabling environment, including organisational structures, to face its future water challenges.